1983

today

Advancing Equity Through Social Justice

By actively recruiting and supporting minority students, Harvard Medical School opened its doors and changed the demographics of its student body.

Although increasing numbers of women students and students of color reflect policies and programs supporting diversity and inclusion, students attending Harvard Medical School have still faced hurdles to medical education. Furthermore, while minority enrollment among students has increased, promotion of faculty members of color has lagged. Acknowledging the importance of diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging, Harvard Medical School has undertaken several initiatives and programs to support faculty, students, trainees, staff, and all who are part of the Harvard Medical School community.

Key Events

Established in 1970, the Pre-Matriculation Summer Program was designed to prepare students from underrepresented backgrounds for success at Harvard Medical School by offering basic science courses. In 1983, the scope of the summer program was broaded to include the opportunity for students to do full-time research in laboratories of medical-area faculty. The program continues to be a success and has expanded to encompass primary-care placements as well as careers in oncology.

The Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health, commonly known as the Heckler Report, marked the first time the U.S. government comprehensively studied the health status of racial and ethnic minorities, elevating minority health onto a national stage. The Heckler Report has served as a driving force for ending health disparities and advancing health equity in America.

The Heckler Report, spearheaded by former Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret M. Heckler (1983-1985), “concluded that health disparities accounted for 60,000 excess deaths each year and that six causes of death accounted for more than 80 percent of mortality among Blacks and other minority populations. It further outlined several recommendations to reduce health disparities and revealed the need to improve data collection among Hispanic, Asian American, and American Indian/Alaska Native populations where national health data were limited or lacking.”

More information on the Heckler Report can be found at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health.

In 1990, the Harvard Medical School Minority Faculty Development Program (MFDP) was established to serve as an umbrella organization for minority recruitment, development and retention initiatives undertaken at HMS and affiliated hospitals under the leadership of Dr. Joan Y. Reede. Before joining the HMS faculty in 1989, Dr. Reede served as the medical director of a Boston community health center, and of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Youth Services. She has also worked as a pediatrician in community and academic health centers, juvenile prisons, and public schools.

The MFDP offers programming to identify and support the needs of individuals and institutions, while also increasing the number of students interested in careers in science and medicine ranging from grade school mentoring initiatives to career development and ladder programs for current faculty.

These long-term efforts continue to lead to increases in the number of underrepresented minority faculty.

The Biomedical Science Careers Program (BSCP) was founded in 1991 by Joan Y. Reede, M.D., M.P.H., M.S., M.B.A, with the aim of increasing the representation of underrepresented minorities in all facets of science and medicine while helping health care institutions, biopharma/biotechnology firms, educational institutions, professional organizations, and private industry members meet their need for a diverse workforce. BSCP was incorporated as a not-for-profit organization in 1994. The founding sponsors of BSCP are the Harvard Medical School Minority Faculty Development Program, the New England Board of Higher Education, and the Massachusetts Medical Society.

The primary objective of all BSCP activities is to identify, inform, support, and provide mentoring for academically outstanding students/fellows, particularly African-American, Hispanic/Latino, and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals. BSCP’s first student conference took place in March 1992 and was attended by 300 high school, college, medical, and graduate minority students. Since its inception, more than 13,000 minority students and 1,200 underrepresented postdoctoral trainees and junior faculty members have participated in BSCP programs. Participants range from high school to postdoctoral level and attend from across the country. Students/fellows attend from over 391 institutions spanning 39 states plus the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Canada, Brazil, Belgium and Australia. They join and return at different levels throughout their academic career.

In January of 1995, Dr. William Silen, Johnson & Johnson Distinguished Professor of Surgery, was named the Faculty Dean for Faculty Development and Diversity. In January 2002, the office was renamed the Office for Diversity and Community Partnership (DICP) and Dr. Reede was appointed Dean for Diversity and Community Partnership.

DICP’s mission is to advance diversity inclusion in health, biomedical, behavioral, and STEM fields that build individual and institutional capacity to achieve excellence, foster innovation, and ensure equity in health locally, nationally, and globally. The office was created to promote recruitment, retention, and advancement of diverse faculty and to oversee all diversity activities involving Harvard Medical School faculty, students, trainees, and staff.

The office supports career development of junior faculty and fellows; trains leaders in academic medicine and health policy; provides programs that address crucial pipeline issues; and sponsors awards and recognitions that reinforce behaviors and practices that are supportive of diversity, inclusion, mentoring, and faculty development.

Based at Harvard Medical School in the Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership, the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University is a one-year, full-time, academic degree-granting program designed to prepare physicians, particularly physicians from groups underrepresented in medicine, to become leaders who improve the health of disadvantaged and vulnerable populations through transforming healthcare delivery systems and promoting innovation in policies, practices, and programs that address health equity and the social determinants of health. Fellows will complete academic work leading to a Master of Public Health degree at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health or a Master of Public Administration at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. The program incorporates the critical skills taught in schools of public health, government, business, and dental medicine with supervised practicum, shadowing, mentorship, leadership forums, and seminar series conducted by Harvard senior faculty and nationally recognized leaders in healthcare delivery systems and public policy.

The Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University welcomed its inaugural class in 1996. To date, 137 fellows have been trained, including those funded by the California Endowment Scholars Program and the Oral Health Fellowship Program (funded by The California Endowment, HRSA, the Dental Service of Massachusetts/Delta Dental Plan, and Harvard School of Dental Medicine).

Joseph B. Martin became Dean of Harvard Medical School in 1997, and one of his first acts as Dean was to open to the campus the doors of the Medical Administration building, which had been closed for many years for "security reasons." This action was symbolic of Dean Martin's commitment to inclusion and transparency on the campus. In his memoir, Dean Martin explains that the opening of the doors was symbolic:

"It represents my priorities for Harvard Medical School. We, in this building will be open and accessible to all our communities."

That fall, the school embraced a new mission statement: "To create and nurture a diverse community of the best people committed to alleviating human suffering caused by disease."

Joan Y. Reede, MD, MPH, MS, MBA was appointed as the first Dean for Diversity and Community Partnership at HMS in 2002, giving her the distinction of being the first Black woman dean and first Black academic dean at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Reede also holds appointments as Professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and is an Assistant in Health Policy at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Reede created and developed more than 20 programs at HMS that aim to address pipeline and leadership issues for minorities and women who are interested in careers in medicine, academic and scientific research, and the healthcare professions.

Dr. Barbara J. McNeil, Harvard Medical School Class of 1966, the Ridley Watts Professor of Health Care Policy, and professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, was named interim Dean of Harvard Medical School in 2007 before Dean Jeffrey S. Flier took office. Dr. McNeil also served as interim dean in 2016 before Dean George Q. Daley took office.

Dr. McNeil has been a member of the Harvard Medical School faculty since 1983 and founding chair of the Harvard Medical School Department of Health Care policy since 1988. She was the first alumna of Harvard Medical School to be promoted to full professor at Harvard Medical School.

Ms. Sandra L. Fenwick was named President of Boston Children’s Hospital in 2008 and was appointed Chief Executive Officer in 2013. She joined Boston Children’s in 1999 as Senior Vice President for Business Development Strategy and was promoted to Chief Operating Officer later that year.

Ms. Fenwick holds a Bachelor’s degree from Simmons College and a Master’s degree in Public Health Services Administration from the University of Texas School of Public Health.

Dr. Elizabeth (Betsy) Nabel, a cardiologist and biomedical researcher, joined Brigham and Women’s Hospital in 2010 as President. A graduate of Weill Cornell Medical College, Dr. Nabel is formerly the director of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the Chief Health and Medical Advisor to the National Football League.

In 2014, the LGBT Office was established as part of the Office of Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership. Although student and faculty-led efforts to support Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) students had existed since the 1980s, the office was Harvard Medical School's official attempt to enhance diversity inclusion while fostering an open, affirming, and welcoming community for LGBT students, staff, faculty, trainees, and fellows at Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Dental Medicine. The goal of the office is to identify key areas of importance, programmatic interventions, and resources that support LGBT issues. The LGBT Advisory Committee advises the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine on key priorities that address issues of importance to the HMS/HSDM LGBT community.

In 2015, during the tenure of Jeffrey S. Flier, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Executive Dean for Administration John Czajkowski established a committee of students, staff, and faculty to seek input from the broader HMS community to inform the creation of a Community Values Statement. This Community Values Initiative explored the core values and principles that embodied the work of the HMS community and articulated how to extend on a daily basis to fulfill the school's mission "to create and nurture a diverse community of the best people committed to leadership in alleviating human suffering caused by disease."

The initiative led to the Community Values statement found here:

"Harvard Medical School is a community dedicated to excellence and leadership in medicine through education, research and clinical care. We aspire to excellence through a commitment to our community values," including collaboration & service, diversity & respect, integrity & accountability, lifelong learning, and wellness & balance.

Dr. Laurie Glimcher became President and CEO of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in 2016, and is the first woman to lead the institution. Glimcher is also Director of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, and the Richard and Susan Smith Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Previously, she was the Stephen and Suzanne Weiss Dean and Professor of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, where she was also the first woman to serve as Dean. Dr. Glimcher is a distinguished immunologist, and Harvard Medical School alumna, class of 1976.

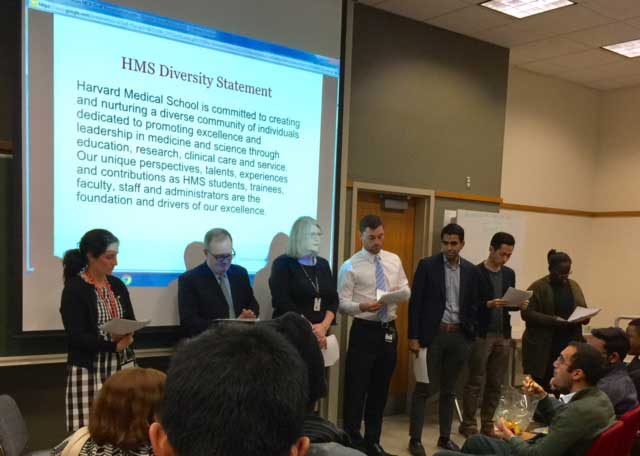

In 2017, Harvard Medical School released a Diversity Statement affirming the school’s commitment to diversity among faculty, staff, students, trainees, and all who are part of the campus community.

The diversity statement confirms that Harvard Medical School seeks to understand, recognize, appreciate, and celebrate differences. You can find Harvard Medical School's diversity statement in its entirety here: https://hms.harvard.edu/about-hmscampus-culturediversity-task-force/harvard-medical-school-diversity-statement

“Harvard Medical School is committed to convening and nurturing a diverse community of individuals dedicated to promoting excellence and leadership in medicine and science through education, research, clinical care and service. Our unique perspectives, talents, experiences and contributions as HMS students, trainees, faculty, staff and administrators are the foundation and drivers of our excellence.”

In February 2016, HMS students formed the Racial Justice Coalition (RJC). In part, the RJC grew out of White Coats for Black Lives, a group who, taking cues from the Black Lives Matter movement, staged die-ins at over seventy medical schools across the country. Students urged medical schools to commit to admitting and supporting minority students as well as supporting communities of color. In the context of the search for a new Dean at HMS, RJC members presented a petition in February 2016 to Harvard University President Drew Gilpin Faust, calling on Faust to choose a dean who would address the lack of diversity at Harvard Medical School.

George Q. Daley was appointed Dean of Harvard Medical School in 2017, and created the Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion to advance Harvard Medical School’s commitment to diversity and inclusion, and to bring together individuals to discuss, evaluate, and advance the mission of diversity at Harvard Medical School.

With input from faculty, students, trainees, fellows, staff and administrators from across the Harvard Medical School community, The HMS Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion focuses on four areas:

- Developing a Harvard Medical School diversity and inclusion vision and policy that are consistent with our mission and values; foster excellence in teaching, research and service; support the multiple dimensions of diversity reflected in our community; and are responsive to regulatory requirements;

- Identifying measures of accountability to assess the achievement of diversity and inclusion goals and expectations, including mechanisms for promoting evidence-based decision making;

- Understanding the landscape of current HMS, HMS-affiliates and Harvard University diversity and inclusion resources and offerings; and

- Prioritizing and exploring areas of diversity and inclusion for deeper investigation, goal-setting and recommendations for action.

The final report for The HMS Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion was released in June 2020.

For more information on The HMS Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion, visit: https://hms.harvard.edu/about-hms/campus-culture/diversity-inclusion

For more information on the Racial Justice Coalition, visit: https://www.statnews.com/2016/02/08/harvard-medical-school-diversity/ and https://snma.hms.harvard.edu/.

On April 17, 2018, over one hundred Harvard Medical School and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health students in white coats, with faculty and staff, staged a “die-in” as part of a nationwide demonstration organized by White Coats for Black Lives. The peaceful protest was put together in the wake of the police shooting of Stephon Clark, a 22-year-old man who was standing in his grandmother’s yard, holding a cell phone.

Demonstration participants said their goal was to continue to bring awareness and attention to social injustice, implicit bias, and violence against Black people by police. National White Coats 4 Black Lives demonstrations began in 2014 after grand jury nonindictment in the cases of the murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

In 2018, Kevin B. Churchwell, MD, Chief Operating Officer (COO) at Boston Children’s Hospital, also took on the role of President. Dr. Churchwell is the first African American President and COO of a Harvard Medical School affiliated hospital. Dr. Churchwell is also the Robert and Dana Smith Associate Professor of Anesthesia at Harvard Medical School.

With input from the campus community, Harvard Medical School updated its mission statement to reflect the work the campus community does to alleviate suffering and create a healthier world for all:

“To nurture a diverse, inclusive community dedicated to alleviating suffering and improving health and well-being for all through excellence in teaching and learning, discovery and scholarship, and service and leadership.”

The new mission statement complements the Harvard Medical School values statement and diversity statement. Learn more about the mission statement here: https://hms.harvard.edu/about-hms/campus-culture/mission-statement-community-values

Key People

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1984

Lisa I. Iezzoni initially enrolled in a master's program in Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She was interested in patient care in addition to global health policy, and so enrolled in Harvard Medical School.

During her first year of medical school, Dr. Iezonni was diagnosed with mulitple sclerosis (MS). She completed her medical degree, and went directly into research rather than internship. Dr. Iezzoni became the first woman to be appointed professor in the department of medicine at Beth Israel Hospital in 1998. She is now the Director of the Mongan Insitute for Health Policy at Massachusetts General Hospital.

"The Americans with Disabilities Act was signed on July 26th, 1990…all of a sudden now, people with disabilities had civil rights. And what happened to me back then could not possibly happen to a Harvard medical student now."

"But what happened that summer when I was taking the two inorganic chemistry semesters was that I’d be jogging along the Charles River, because I liked to be very physically active, and I didn’t know where my legs were in space."

"I had a spinal tap. And at the end of that month, I was diagnosed with MS."

"Now, this was back in January of 1981…this was the first time that I realized that this new diagnosis is going to carry implications beyond my health; it’s going to carry implications for how people are going to treat me and react to me…"

"And he paused and he kind of steepled his fingers and he said, “Well, there’s too many doctors in the country right now for us to worry about training a handicapped physician…"

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1987

Valerie Montgomery Rice, a Georgia native, attended the Georgia Institute of Technology, where she received her bachelor's degree in chemistry. She studied medicine at Harvard Medical School, and graduated in 1987. In 2011, she became Dean and Executive Vice President for Morehouse School of Medicine.

“Well, the decision to go to medicine, as I said, was impulsive. And so when I came back, after my co-op experience, with this job opportunity offer in hand and recognizing that I didn’t want to be an engineer, I went over to Spelman College -- because at that time, Georgia Tech did not have a formal premed program -- and told them my idea that I thought I would go to medical school.”

“I wanted to do reproductive endocrinology. And what really was the key ingredient that probably enticed me... So I did that rotation toward the end of all my rotation. Because I thought, for sure, that I was going to be a neurosurgeon, when I went to medical school.”

“I think about the things that probably made the biggest difference for my experience at Harvard Medical School -- was that I felt very supported. So I felt that there was clearly the opportunity to do anything that I wanted to do.”

“When I started working in women’s health, I started working as an advocate for women of color -- looking at how they were disproportionately not represented in clinical trials, looking at diseases that disproportionally impacted women of color based on their reproductive function or endocrinological function.”

“I think I had a very great experience at Harvard Medical School, so much so that, you know, my daughter’s a first-year student there -- so she’s in the first-year class now at HMS. And what I believe that Harvard Medical School allowed me to do was to blossom. It affirmed for me what was possible through hard work.“

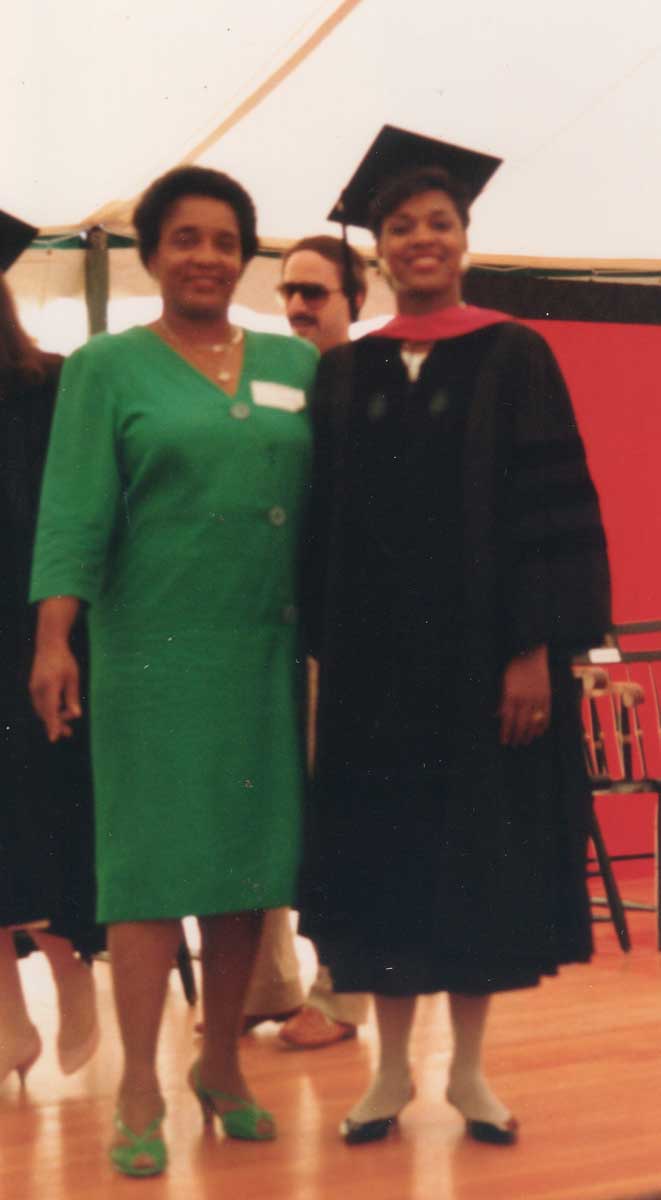

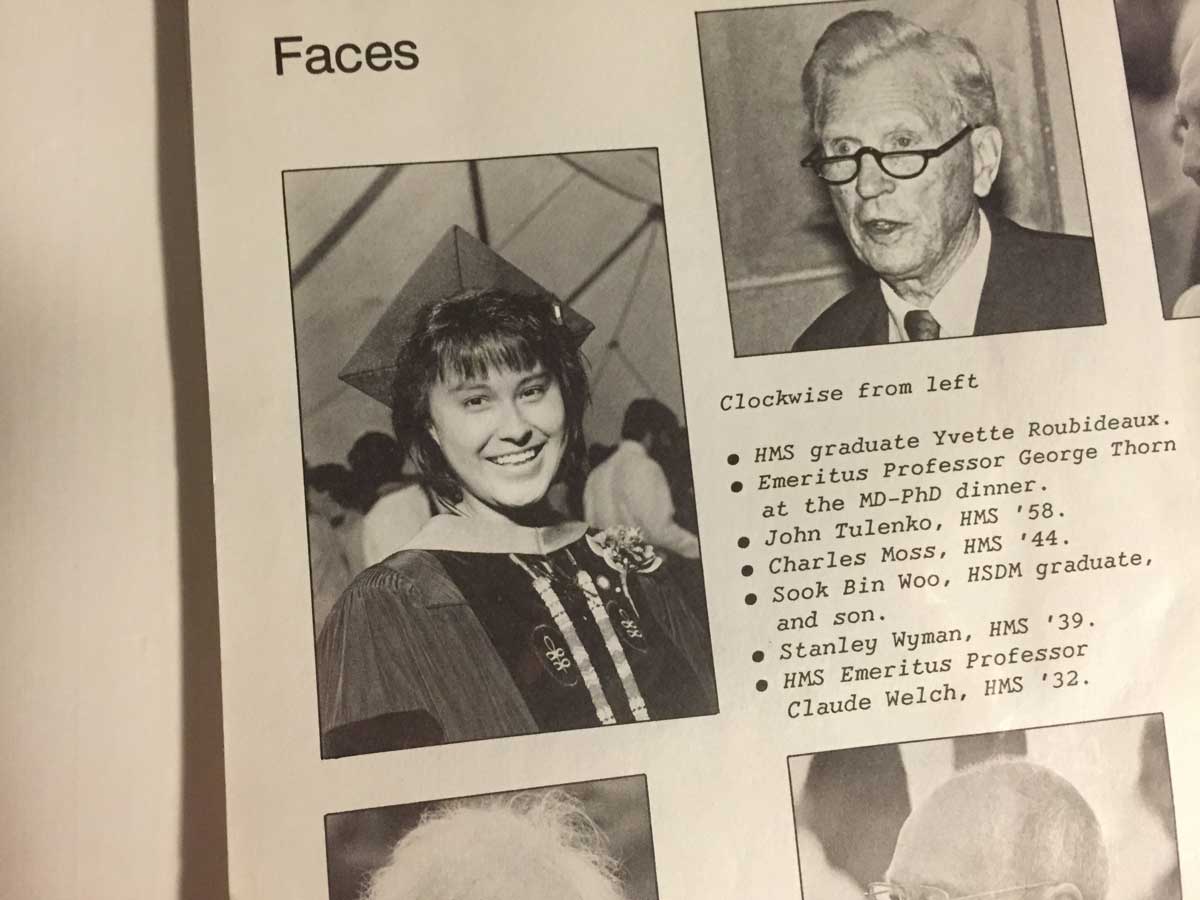

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1989

Yvette Roubideaux grew up in western South Dakota, and is a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. She attended Harvard College, and graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1989. She also completed her Master of Public Health degree at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Dr. Roubideaux worked in clinical practice for the Indian Health Service, conducted extensive research on American Indian health issues, and in 2009, was appointed as Director of the Indian Health Service in the administration of President Barack Obama. She was the first woman to serve in this position.

“I am a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. And also Standing Rock Sioux. … I first decided to become a doctor when I was thinking about careers in high school. And I recalled the incredible need that there was for doctors in the Indian Health Service.”

“I have known from the day I decided I wanted to be a doctor that I wanted to go back and practice medicine in the Indian Health Service. I wasn’t sure what kind of doctor I wanted to be, except that the doctors they needed were primary care doctors. And Harvard didn’t have a family medicine rotation.”

“A faculty mentor told me, or said the line, “You know, it’s a shame you’re wasting your Harvard education if you’re only going to go back and work on an Indian Reservation.””

“It was really a turning point for me to say, well, you know, obviously that faculty mentor did not understand the need, and did not understand that American Indian/Alaskan Native patients deserve the best trained doctors. And actually, they probably deserved more better trained doctors because of the complexity of their situation and their illnesses and the challenges and the system.”

“Back in the 1980s, there was always the unspoken fear that people thought that we were admitted because of our race and not necessarily because of our potential or our skills.”

“So, for me, it feels like … -- whenever I visit Harvard, it feels like the climate is so much better. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

“I became very interested in, you know, the challenges of diabetes in American Indians. But I also saw the limitations and the frustrations of working in an underfunded system.”

“In 2009, I got the call to join the Obama Administration, and was nominated and Senate confirmed as the Director of the Indian Health Service.”

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1990

Carmon Davis is a pediatrician in General Pediatrics at Boston Children’s Hospital and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Davis’ full oral history is available to researchers at the Center for the History of Medicine. Contact chm@hms.harvard.edu for more information.

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1993

Dr. Valerae O. Lewis grew up in the Bronx, New York City, and from a young age wanted to be a doctor. She attended Yale University, where she graduated with a degree in Psychobiology. She graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1993 with honors and completed her orthopaedic training at the Harvard Combined Orthopaedic Residency Program.

Since 2000, Dr. Lewis has been at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center where she continues to blaze trails. She was named the Dr. John Murray Professor in Orthopaedic Oncology in 2010. She was the first African American woman to be awarded the MD Anderson Faculty Achievement Award in Patient Care (2012); first woman to chair an orthopaedic department at a freestanding cancer center (2014); first woman to chair an orthopaedic department in The University of Texas System (2014); and the first African American woman to Chair an Orthopaedic Surgery Department.

“I never wanted to be anything else but a doctor. I mean, I will say that I wanted to own a gas station, and I wanted to be a carpenter on weekends, but I always knew that I wanted to be a doctor. … My dad …still made house calls probably till his late seventies.”

“So I remember mailing in the Yale postcard and putting no on the Harvard one. And then I came back to my -- the car, and my mom asked where I said I was gonna go, and I said Yale. And she just started crying, and she goes, “I just wanted one of my daughters to go to Harvard!” So I felt really bad, ’cause it was probably a silly argument, and so I said, “OK, I promise I’ll go to Harvard Medical School.””

“So one of the things I remember is you’re applying to residency program, you know, and as a women -- woman, and as an African American woman applying to orthopedics, it can be a little daunting ’cause it’s generally all white male. And I remember I read the -- one of the recommendations from one of the orthopedic faculty, and just the last -- the last paragraph, but it was glowing. And it just made me feel like I can do this, like I am just as good as the rest of these boys out here.”

“Harvard’s orthopedic program is actually a combination of Mass General, BI Deaconess, Brigham, and Texas Children... And that was a great residency. It was a very diverse residency, compared to other residencies at the time. There was at least one to two women a year, and one to two African Americans or people of color a year. Really, we have Gus White and Henry Mankin to thank for that.”

“I really started as assistant professor and worked my way up to become the John Murray Professor of Orthopedic Oncology, but also chair of an orthopedic oncology department. And it was exciting, ’cause there are no other black women chairs of orthopedics, and there aren’t any other women chairs in surgery in the whole UT system, and UT system is very large. “

“But what’s interesting is -- and I included it in my talk -- all the stories, or many of the stories, of the African American physicians back in the early ’60s, you know, even early ’20s, the obstacles they’d face are still present with many of the African Americans today.“

“As I get older, you realize the importance of including and bringing up more people like yourself, because as you get higher and higher in the administrative echelon you realize there are fewer and fewer people who look like you. And then you combine that with all the studies that show that diversity breeds innovation, and innovation breeds success, that you’re even more encouraged to go and make a diverse workforce or a diverse administrative team.”

Graduated Harvard Medical School in 1994

Born in 1965, Robert Lee “Bobby” Satcher, Jr. grew up in Hampton, Virginia. He earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School in 1994, and his BS and PhD in chemical engineering from MIT in 1986 and 1993, respectively. Dr. Satcher realized part three of his dream to become an engineer, a physician and an astronaut, in 2006.

In 2009, Astronaut Robert Satcher became the first orthopedic surgeon and first Black male physician in space during the STS-129 NASA Space Shuttle mission to the International Space Station. In his 11-day mission on the Space Shuttle Atlantis, Dr. Satcher participated in 2 spacewalks at the International Space Station, and used his surgical skills to repair two robotic arms on the space station’s exterior. He also installed an antenna to improve satellite communication and served as the crew’s medical doctor.

Dr. Robert Satcher is now an associate professor of orthopaedic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. He is also working to build a cancer center in sub-Saharan Africa.

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1996

Dr. Kathryn Hall is Associate Molecular Biologist and Assistant Professor in the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Director of Placebo Genetics in the Program in Placebo Studies at Harvard Medical School (HMS). After receiving her PhD in Microbiology and Molecular Genetics from Harvard University she spent 10 years in the biotech industry tackling problems in drug discovery and development, first at Wyeth (now Pfizer) and then at Millennium Pharmaceuticals (now Takeda), where she became an Associate Director of Drug Development. Dr. Hall returned to HMS in 2010, joining the Fellowship in Integrative Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in 2012, and receiving a Master’s in Public Health from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in 2014. Dr. Hall was the 2015 Harvard Catalyst Program for Faculty Development and Diversity Inclusion (PFDD) faculty fellow and is the 2019 BWH Minority Faculty Career Development Awardee.

She was recently awarded a Radcliffe Exploratory Program grant which supported the groundbreaking Placebome in Clinical Trials and Medicine Conference in 2019. Her research has been the focus of numerous articles including features on BBC and in Science, The Atlantic, New York Times, The Economist and Discover magazines. Dr. Hall also has a Masters in Documentary Film from Emerson College.

“My goal was to get to industry, so I could, you know, make a company to employ Jamaicans, and we would, you know, become self-sufficient in this pharma industry in Jamaica.” (time)

“I was one of the founding members of MBSH, which is Minority Biomedical Scientists of Harvard.” (time)

“In the first meeting, they called all us graduate students together, I think there were about five of us in my class. And they said, they showed us a graph, and on it, it showed the enrollment, the PhD enrollment, like over the last, you know, 5 to 10 years. And they show it going up, up, up, up, up, and then it just plummets down. And they asked us if we had any idea why it would have plummeted down. And of course, it was exactly the year when Dr. Amos retired.” (time)

“I had registered for a conference here, and in line, and the person is checking me in, and they say to me, “Are you signing in for somebody else?” And I say to them, “What is it about me that makes you think I’m signing in for someone else?”” (time)

“And I thought wow, why don’t I do that, and do all the things I’ve ever wanted to do? And I made a list of the things that I always wanted to do in life, and they were, I always wanted to be a filmmaker, make a, you know, a film. I always wanted to renovate a house. I always wanted to write a book. I always wanted to have my own business.” (time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1996

Dr. Thomas Sequist is Associate Professor of Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Sequist is chief quality and safety officer at Partners HealthCare, Director of the Four Directions Summer Research Program at Harvard Medical School, and medical director of the Brigham and Women's Hospital Physician Outreach Program with the Indian Health Service. He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1999.

Interview Transcript | Part 1 of 2 (pdf)

Interview Transcript | Part 2 of 2 (pdf)

“It was the fall of my junior year and sort of realized I don’t know that I want to do this I think I might want to go to a medical school.” (time)

“The short answer of like why did I end up at Harvard, is because it sort of felt right to me.” (time)

“The main set of activities that we did back then was something called the Four Directions Summer Research Program... The First summer it ran actually was the summer before I got to Harvard in 1994.” (time)

“One of the big things that has changed is that when we were first running that program way back in the mid-’90s, we were only really a year or two more advanced than the students who were coming here. We had made -- with one big difference is that we had got into medical school, which was really exciting. … So I am now – you know, 25 years later, I am still the primary person who sits down and meets with these students…”(time)

“What I really always had wanted to do when I first was in medical school was, I wanted to become a physician and go back and work in the Indian Health Service on a reservation. And I obviously didn’t do that … maybe I could contribute to the Native communities in different way…” (time)

“I think Boston has changed a bunch over the past 25 years that I’ve been here, but I think it still has a lot of issues to confront… But at the end of the day, if you ask any person of color in this city, Does this feel like a welcoming environment, I think all too often, unfortunately, you’re going to hear, No, it doesn’t feel totally welcome.” (time)

“if you don’t support people who are interested in community outreach -- all of the stuff that Joan Reede’s office supports -- if you don’t support people who are interested in research that’s not in a lab but is interested in research like I do -- like health equity, health policy research -- you are really limiting the type of person who might want to come to Harvard and contribute to our community.”(time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 2001

Dr. Saldaña is Dean for Students at Harvard Medical School and oversees the Office of Student Affairs. Dr. Saldaña is a clinical cardiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2001.

“My job was to be a student. Growing up, they said, “Work hard in school,” because my parents didn’t have a chance to go to school, so that’s something that we really valued growing up, and I think that’s probably what led me to pursue a career in medicine.” (time)

“As a kid you’re kind of always at the bottom of the totem pole, of the hierarchy, and having this special talent of speaking English … So I think feeling like I had a special talent as a kid, where I could help, and I would help random people too… I would translate for random people on the street. And I thought that was something very special I could use to help others, my mom really kind of instilled that idea of helping others and generosity and looking out for one another.” (time)

“I met some great mentors, and eventually I found a little niche in that group that was called Chicanos in Health Education. Students that were of very similar background who had the same dream, and really we supported each other, and all of us really were successful in getting into medical school…” (time)

“I’ve seen ups and downs, to be honest. As a student I felt that |LS|diversity and inclusion] was always valued.” (time)

“But I think it’s always a challenge that we hit certain ceilings that we haven’t been able to go above. And I think that’s probably the next step, is how can we make sure that all of our institutions have best practices, and how can we break some of those ceilings.” (time)

“But you can’t really do without all the mentors out there so maybe if anybody is listening or reading, |LS|I’m] just encouraging |LS|you] to reach out to folks, because you will make an incredible difference in someone’s life.” (time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 2004

Dr. Washington is Associate Clinical Professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine in the Department of Reproductive Medicine. Dr. Washington also works as an abortion provider at Planned Parenthood and was formerly Medical Director and Chief Medical Officer of Planned Parenthood of the Pacific Southwest. She graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2004.

In 2001, student Sierra Washington co-founded FABRIC, an annual event celebrating the diverse backgrounds and talents of students in the Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Dental Medicine community. Originally founded to explore the artistic and cultural traditions of the African diaspora, FABRIC has evolved through the years to include art forms and cultures from around the world. First-year students perform during Revisit week and invite newly admitted students to join the community at the two schools. For more information about FABRIC visit: https://hms.harvard.edu/news/show-welcome

“I had a lot of difficulty assimilating into the United States, mostly because the way that people conceive and conceptualize race really informs all of society, and I just wasn’t really ready for that. So I had a pretty tough time in university understanding how race just could permeate everything, everything that you do, and I felt a lot of pressure on campus to conform.” (time)

“I think I knew from very early on that I was going to go into medicine.” (time)

“After my trip to Thailand, it felt like, you know, I just, I know I want to do something in the world to alleviate poverty and suffering.” (time)

“The reason I ended up choosing going to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is because I knew I wanted to work in Africa, and I knew I wanted to do work on HIV.” (time)

“I hated internal medicine; I hated it so much. I felt like, first of all, the nurses were mean and racist …, and treated me horribly. And second of all, I did not like the culture of like, OK, we spend five minutes with the patient, and then we sit in a room, a conference room, and discuss for hours, you know, should we do this, or should we do that? Is it this, or is it that? … I almost dropped out of medical school after that.” (time)

“I remember writing home and saying, like, this is 2000, and women are still dying in childbirth for no reason, you know, other than like, there’s just not enough resources being put to it.” (time)

“I just remember feeling like, you know, this is like a very impoverished side just on the backside of the hill, and you know, we’re right next to these ivory towers; it’s kind of crazy. One day I stopped into this school, and there was this guy who was like, yeah, I’d love for there to be an afterschool science program for young girls.” (time)

“We kind of started this curriculum project, and through that, we had this idea of like, maybe we should fundraise for a specific disease that strikes the black community. And, being an artist, I was like, why don’t we do an art show? Why don’t we showcase the fabric of the black community here in the Longwood area, because so many people, as I mentioned earlier, came to Harvard with already this incredible talent in something else, and decided to do medicine.” (time)

“How does that exist in 2000? Like, this is like, you know, this is pre-civil rights style segregation. And then that was borne out in the hospitals.” (time)

“Harvard’s no different than any other institution in having those things happen, other than it’s been around longer and has more entrenched this white privilege.” (time)

“And that was a mind-blowing experience, because things like, why was it easier for women to get an IUD in Rwanda than in the Bronx?” (time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 2018

Dr. Tate graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2018 and served as President of the Harvard Medical School Chapter of the Student National Medical Association. Dr. Tate also hosts, produces, and edits the Dear Premed podcast, and was a fellow for One Heart World-Wide, a nonprofit that implements maternal and neonatal mortality prevention programs in areas where women often die alone at home giving birth. Dr. Tate graduated from Dartmouth College in 2012 and is currently an OBGYN Resident at McGaw Northwestern.

“I’ve known that I wanted to be a doctor since I was a little girl. More specifically, I knew that I wanted to be an obstetrician.” (time)

“I was the director of a program called the Dartmouth Alliance for Children of Color, where we brought children who were African, or African American children, mostly children who are adopted into white families, in the Upper Valley area, who come to our school once a week and they hang out with people that look like them.” (time)

“I learned about this organization that was doing work to reduce maternal, or you know, maternal and infant mortality, morbidity, things that were preventable. So they specialize in working in very remote and rural areas around the world.” (time)

“What does it mean for my community to be able to have been trained at Harvard Medical School, you know? That was a big part of my calculus in deciding to come here, and thinking about how I could then use this platform, use this privilege, for the communities that I care about.” (time)

“In my entering class, we came in together, 15 students, and said that we’re just going to make this place what we want it to be. We’re going to make this community strong, and we’re very intentional, and very deliberate about that.” (time)

“We also wanted to make sure that our voices were heard here at the medical school, and across all different levels of the administration.” (time)

“For them to just light up when they see this black girl walking in the room with the rest of her team, which usually was mostly white, and to just look at me with such pride, and such joy in their eyes.” (time)

“I think that the medical school has also done a good job of recognizing that we’re not where we need to be, and so, we have to figure out what to do to make it better.” (time)

“I want my work to center around racial and ethnic inequities in birth outcomes. So whether that’s maternal mortality or infant mortality, or morbidity in either of those things, I want that to be the centerpiece of the work that I do.” (time)