Timeline

Harvard School

of Dental Medicine/Oral

Health History

ABOUT

Harvard School of Dental Medicine was established on July 17, 1867, by vote of the Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College. It was the first dental school in the United States to be affiliated with a university and its medical school. The school was also the first to confer the Dentariae Medicinae Doctoris (DMD) degree.

The school’s first dean, Dr. Nathan Cooley Keep, was a prominent Boston physician and proponent of dental education.

The school’s commitment to diversity and inclusion is as old as the school itself, boasting the first Black graduate of a dental school in America, as well as the first Black dental instructor.

Timeline

In 1840, the Baltimore College of Dental surgery was founded as an independent institution and the first dental college in the world. Two dental practitioners, Dr. Horace H. Hayden and Dr. Chapin A. Harris, played a major role in establishing and promoting formal dental education as well as the development of dentistry as a profession. Although the school was the first of its kind in the world, it was not associated with a medical college.

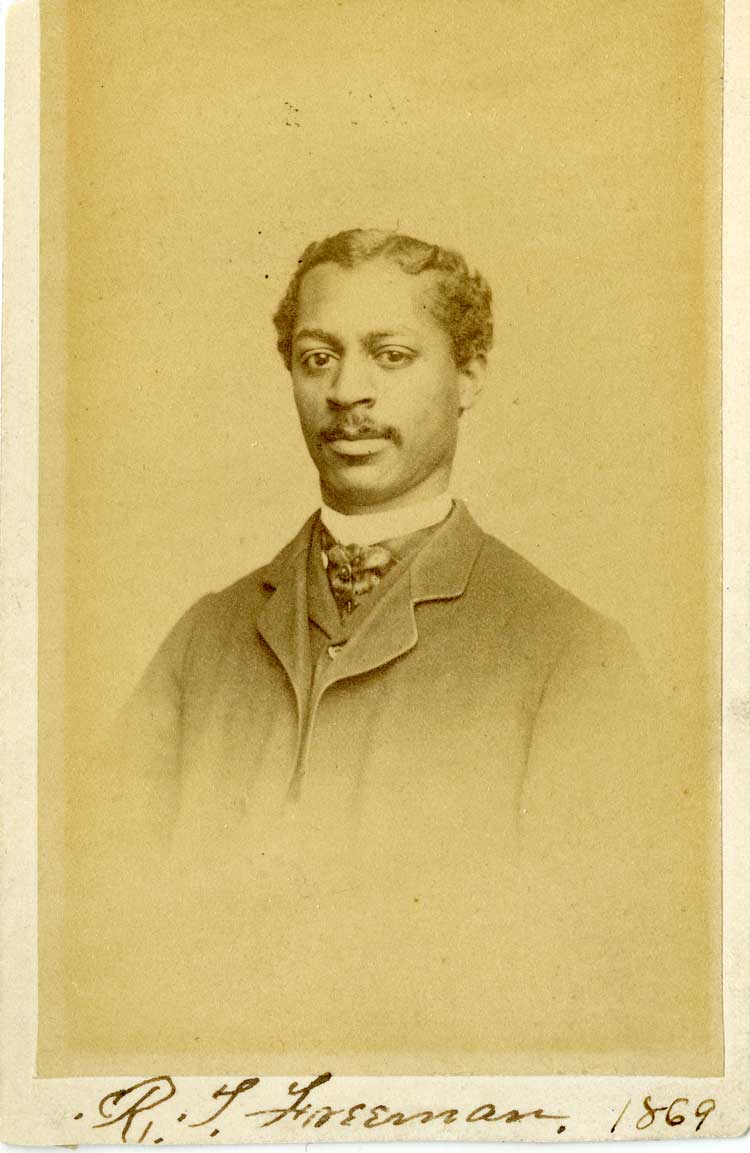

The dental school, after deliberate internal discussion among its faculty, declared from the beginning that it would be founded upon notions of tolerance and inclusion. Of the 1868 admission and success of Robert Tanner Freeman, Dean Leroy M.S. Miner would later recount: “Robert Tanner Freeman, a colored man who had been rejected by two other dental schools on account of his race, was another successful candidate. The dental faculty maintained that right and justice should be placed above expediency and insisted that intolerance must not be permitted. Dr. Freeman was the first of his race to receive in America a dental school of education and dental degree.”

From Leroy M.S. Miner, “The Dental School,” in Samuel Eliot Morison, ed., The Development of Harvard University since the Inauguration of President Eliot, 1869-1929 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1930), p. 597. Historian Clifton Orrin Dummett would later remark of HSDM and its stance on admitting and training black students: “This school deserves the credit for setting the precedent in liberalism, justice, and the true scientific spirit.” In Dummett, The Growth and Development of the Negro in Dentistry in the United States (Chicago: The Stanek Press, on behalf of the National Dental Association, 1952), p. 7.

Robert Tanner Freeman was the first African American to receive a degree in dentistry from an academic institution in the United States. He graduated from Harvard School of Dental Medicine in 1869. Read more on Dr. Freeman below, under Key People.

George Franklin Grant, DMD, the second African American to graduate from the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, became the first African American faculty member at Harvard University in 1874. Read more on Dr. Grant below, under Key People.

In 1881, fourteen years after the establishment of the Howard University Medical School, Howard University established the Dental College, which was the first Black dental college in America and only the fifth dental school in the United States. From its establishment, the school was dedicated to providing dental care to African Americans.

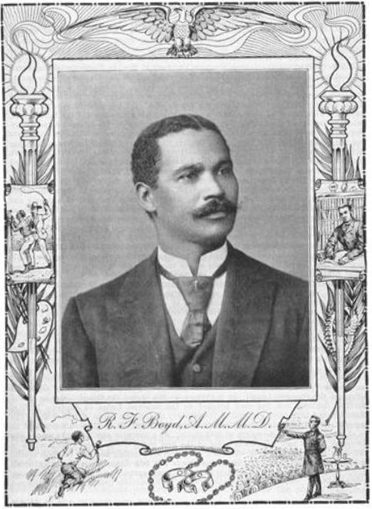

The Meharry Medical College School of Dentistry was established in 1886 in Nashville, Tennessee, ten years after the Meharry Medical Department of Tennessee was created. The Dental program was to “provide the Colored people of the South with an opportunity for thoroughly preparing themselves for the practice of dentistry,” and admitted nine students in its first class. The first graduates were awarded degrees just one year later, as three of the students were physicians and exempt from the first year of dental requirements. Those graduates were: Henry T. Noel of Tennessee; Robert Fulton Boyd of Tennessee; and John Wesley Anderson of Texas.

Created in 1895 after years of attempts by Black physicians to integrate the American Medical Association, The National Association of Colored Physicians, Dentists, and Pharmacists was created in 1895 in Atlanta, Georgia. Robert F. Boyd, M.D., D.DS. was the organization’s first president. See: The Creation of the National Medical Association (in the Historical Context section).

The Washington Society of Colored Dentists was formed on November 14, 1900. The group changed its name in 1907 to honor the first Black dental college graduate, becoming the Robert T. Freeman Dental Society. This group, along with other early regional and national efforts, merged to become the National Dental Association in 1932. See https://ndaonline.org/about-nda/ for more information.

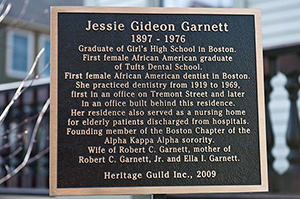

Jessie Gideon Garnett (1897—1976) was 11 years of age when she moved to Boston from Nova Scotia with her family. Jessie Gideon graduated from Girl’s High School in Boston and then Tufts College in Medford, Massachusetts. During her matriculation at Tufts she was accepted to the Tufts Dental School. In 1920, she graduated from Tufts School of Dental Medicine earning a Doctor of Dental Medicine degree, becoming the first African American woman to graduate from the school and the first African American woman dentist in Boston.

Dr. Gideon Garnett’s dental practice was initially located on Tremont Street, prior to its 1922 relocation to Columbus Avenue. In 1929, she moved her home and dental practice to 80 Munroe Street in Roxbury. Dr. Jessie Gideon Garnett practiced dentistry in Boston for nearly 50 years, until her retirement in 1969. In 2009, the Boston Heritage Guild honored Dr. Gideon Garnett, recognizing her achievements and unveiling a plaque marking the historic Victorian home. The Boston landmark is now a stop on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trial.

More information about Dr. Jessie Gideon Garnett can be found here.

Founded in 1990 in Texas, the Hispanic Dental Association is a national, non-profit 501(c)3 organization comprised of oral health professionals and students dedicated to promoting and improving the oral health of the Hispanic community and providing advocacy for Hispanic oral health professionals across the US.

As the leading voice for Hispanic oral health, the Association provides service, education, advocacy, and leadership for elimination of oral health disparities in the Hispanic community.

The Society of American Indian Dentists (SAID) is a national, non-profit organization comprised of oral health professionals and students dedicated to promoting and improving the oral health of the American Indian/Alaskan Native community and providing advocacy for American Indian/Alaskan Native dental professionals across the United States. It was established in 1990 by Dr. George Blue Spruce, the first American Indian dentist, and has over 250 members.

Joseph Louis Henry (d. 2011) received his degree from Howard University’s College of Dentistry and a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois. As a faculty member at Howard College of Dentistry, he was Director of Clinics and Coordinator of Research, and in 1966, Dean. In 1975, Dr. Paul Goldhaber, Dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, recruited Dr. Henry to Harvard to become Professor of Oral Medicine, Department Chair, and Associate Dean for External Affairs. From 1990 to 1991, Dr. Henry served as Interim Dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine.

Dr. Henry was the first Black professor on the Harvard School of Dental Medicine faculty. He is credited with stewarding the School of Dental Medicine through a period of transition that enabled it to successfully retain its position as the first dental school established within a University setting.

The Joseph L. Henry Oral Health Fellowship in Minority Health Policy was established in the Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership in 2005.

Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General was released in 2000 by Surgeon General David Satcher. It was the first ever Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health and meant to inform the American people about how crucial oral health is to overall health. Although the report acknowledged that progress had been made in the 20th century, it also reported that significant oral health disparities exist between different racial/ethnic groups. It concluded that although common dental diseases are preventable, many people face barriers that prevent their access to oral health care.

To read the report, visit: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/surgeon-general.

The Joseph L. Henry Oral Health Fellowship in Minority Health Policy was established in the Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership in 2005. The Fellowship honors the legacy of Dr. Joseph L. Henry by preparing the next generation of leaders in minority health and minority health policy.

The Joseph L. Henry Oral Health Program is supported by the Dental Service of Massachusetts/Delta Dental Plan and previously the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) through a cooperative agreement between the Office of Minority Health and Minority Faculty Development Program at Harvard Medical School. The Oral Health Program is an academic degree-granting program, designed to create oral health leaders, particularly oral health leaders from groups underrepresented in medicine, who will pursue careers in health policy, public health practice and academia. The program is intended to incorporate the critical skills taught in schools of public health, government, business, and dental medicine with supervised practicum, leadership forums and seminar series conducted by leading scholars and nationally recognized leaders in minority health and public policy.

Joseph L. Henry Oral Health Fellows 2001–2020

Phillip Woods | Cynthia Hodge | Brian Swann | Shanta Richardson

E. Elon Joffre | Christina Rosenthal | Shanele Williams | Mehedia Haque

In February 2007, 12-year-old, seventh grader Deamonte Driver died after complications from an abscessed tooth. His mother, Alyce, who worked a low-paying job, could not find a dentist who would accept Medicaid and perform the routine $80 extraction to treat Deamonte's toothache. As a result, bacteria from the untreated tooth infection spread to his brain. After two surgeries and six weeks of hospital care, Deamonte died. His operations, hospital care and therapy totaled approximately $250,000.

Tooth decay is the most common chronic childhood disease – five times more common than asthma.

A 2011 Child Watch Column noted, “Since Deamonte’s death, Congress has recognized dental coverage as an important component of comprehensive care for children, enacting major policy changes to improve dental coverage for children. In 2009, the reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) required states to provide dental coverage to enrolled children, and gave states the option to provide dental benefits to certain children who do not qualify for full CHIP coverage. In 2010, the health reform bill known as the Affordable Care Act required that all insurance plans to be offered through new health insurance exchanges starting in 2014 include oral care for children, and prohibited these insurers from charging out of pocket expenses for preventive pediatric oral health services. These two new requirements alone will give millions of children financial access to dental health services, many for the first time.”

Additionally, in 2011 Deamonte’s home state of Maryland instituted a mobile pediatric dentistry project called the Deamonte Driver Dental Project Mobile Unit. This large van is a mobile pediatric dental clinic that takes oral health care to those in need.

Dr. Peggy Timothé was appointed the first Director of the Office of Diversity Inclusion at Harvard School of Dental Medicine in 2013. In 2015 she was awarded the Michael Shannon, MD, MPH Excellence in Mentoring Award. The award is given to those making significant contributions to mentoring socioeconomically disadvantaged students. Dr. Timothé was also an assistant professor in the Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Sciences at Harvard School of Dental Medicine. She severed as director of the Office of Diversity Inclusion at HSDM for three years, before accepting a position at Texas A&M University.

Josephine Kim, PhD, succeeded Dr. Timothé as Director of Diversity Inclusion at HSDM until her departure in 2019. Dr. Kim currently has a dual faculty appointment in Prevention Science and Practice/CAS in Counseling programs at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and in the Department of Oral Health Policy and Epidemiology at Harvard School of Dental Medicine. She is also on faculty at the Center for Cross-Cultural Student Emotional Wellness at Massachusetts General Hospital.

University of Rwanda graduates its inaugural class of dentists in the Fall of 2018. The seven and a half year journey began in 2011 when Harvard School of Dental Medicine (HSDM) became a leading partner in the effort to launch the new dental school and bachelor of dental surgery degree program at the University. Ten students graduated from the five-year program the first year, increasing the number of registered dentists in Rwanda by more than 25 percent. This milestone provides greater access to oral health in a country of 12 million people.

The initiative started with Partners In Health (PIH), the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and the Rwandan ministries of health and education. Together, the entities launched the Rwanda Human Resources for Health (HRH) Program – a program to advance medical education and improve health care delivery systems in the country.

Oral health disparities are profound in the United States. Despite major improvements in oral health for the population as a whole, oral health disparities exist for many racial and ethnic groups, by socioeconomic status, gender, age and geographic location.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Massachusetts Coalition for Oral Health, some of the oral health disparities that exist include:

- “Overall Racial and Ethnic Disparity. Non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians and Alaska Natives generally have the poorest oral health of any racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

- Children and Tooth Decay. The greatest racial and ethnic disparity among children aged 2–4 years and aged 6–8 years is seen in Mexican American and Black, non-Hispanic children.

- Adults and Untreated Tooth Decay. Blacks, non-Hispanics, and Mexican Americans aged 35–44 years, experience untreated tooth decay nearly twice as much as White, non-Hispanics.

- Tooth Decay and Education. Adults aged 35–44 years with less than a high school education experience untreated tooth decay nearly three times that of adults with at least some college education.

- In addition, adults aged 35–44 years with less than a high school education experience destructive periodontal (gum) disease nearly three times that of adults with a least some college education.

- Adults and Oral Cancer. The 5–year survival rate is lower for oral pharyngeal (throat) cancers among Black men than Whites (36% versus 61%).

- Adults and Periodontitis. 47.2% of U.S. adults have some form of periodontal disease. In adults aged 65 and older, 70.1% have periodontal disease.

- Periodontal Disease is higher in men than women, and greatest among Mexican Americans and Non-Hispanic Blacks, and those with less than a high school education.

Healthy People 2020 is the nation’s framework to improve the health of all Americans with the goals to increase quality and years of healthy life, and eliminate health disparities. More information about Healthy People 2020, the interventions, and other works to eliminate oral health disparities online:

The Status of Oral Disease in Massachusetts: A Great Unmet Need 2009, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2009

Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations, The National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine, 2011

Disparities in Oral Health, Massachusetts Coalition for Oral Health, 2014

Disparities in Oral Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016

Disparities in Dental Health and Access to Care, Article, June 27, 2017, The PEW Charitable Trusts

Oral Health Disparities: A Perspective From the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, PMC U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health, 2017

Healthy People 2020, HealthyPeople.gov, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; view HP2020 Data for Oral Health

Dr. Vicki Rosen, Professor and Chair of the Department of Developmental Biology, was named Interim Dean of Harvard School of Dental Medicine in January 2020. Dr. Rosen’s career at HSDM began in 2001. She is a leading faculty member in the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and co-leader of the HSDM PhD Program in Biological Sciences in Dental Medicine. Prior to Harvard, Dr. Rosen was a scientist at Genetics Institute, a biotechnology company where she worked on a research team to identify bone morphogenetic protein genes in 1988. Dr. Rosen co-chaired the search committee for a new dean of HSDM and will end her service as acting dean on August 31, 2020. William Giannobile, DDS, MS, DMSc takes the helm on September 1, 2020.

Dr. Vincenzo G. Terán began his appointment as the third Director of the Office of Diversity and Inclusion at Harvard School of Dental Medicine in January, 2020. He received his doctorate in clinical psychology from William James College and completed his postdoctoral fellowship at Cambridge Health Alliance/Harvard Medical School. Dr. Terán served as President of the American Psychological Association’s Section of Clinical Psychology of Ethnic Minorities and has held leadership roles aimed at fostering diversity and inclusion in the field of psychology. In addition to teaching, clinical practice, and research in professional psychology, he is passionate about cultivating diversity and inclusion in academic and healthcare settings. Dr. Terán is an Instructor of Oral Health Policy and Epidemiology.

In April 2020, William V. Giannobile, DDS, MS, DMSc, was named Dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine. He is an educator and leader in the field of periodontology and an internationally recognized scholar in oral regenerative medicine, tissue engineering, and precision medicine.

Dr. Giannobile will take the helm on September 1, 2020, succeeding Dr. R. Bruce Donoff who served as dean for 28 years and retired in December, 2019. Interim Dean, Vicki Rosen, PhD, will continue to lead the school until August 31, 2020. Dr. Giannobile is currently the Najjar Endowed Professor and Chair of the Department of Periodntics and Oral Medicine at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Key People

Emeline Roberts Jones was the first woman to practice dentistry in the United States. Born in 1838, Jones married a dentist, Dr. Daniel Jones, and clandestinely trained herself to fill and extract teeth. Her husband, once resistant to teaching her, allowed her to practice with him at his office in Danielsonville, Connecticut in 1855. In 1859, she became his partner and was reputed to be a skilled dentist.

After her husband’s death, she continued to practice dentistry, often traveling with a portable dentist’s chair throughout Connecticut and Rhode Island to support her family. She maintained a practice in New Haven, Connecticut from 1876 until her retirement in 1915.

Lucy Hobbs Taylor was the first woman to graduate from dental school. Born in 1833, Taylor attended the Franklin Academy in New York. She taught for ten years in Michigan, and in 1859 moved to Cincinnati where she applied to Eclectic Medical College. She was denied based on her gender, although she studied privately under the supervision of a teacher from the school. She then applied to the Ohio College of Dentistry, where again, she was refused admission because of her gender. Again, she studied under a private program with a professor from the school. She applied to the dentistry program again, and was again rejected, so she opened her own practice in Cincinnati in 1861. When the Ohio College of Dentistry decided to accept women, she matriculated as a senior in 1865 because of her experience and graduated in 1866, becoming the first woman in the world to earn a doctorate in dentistry.

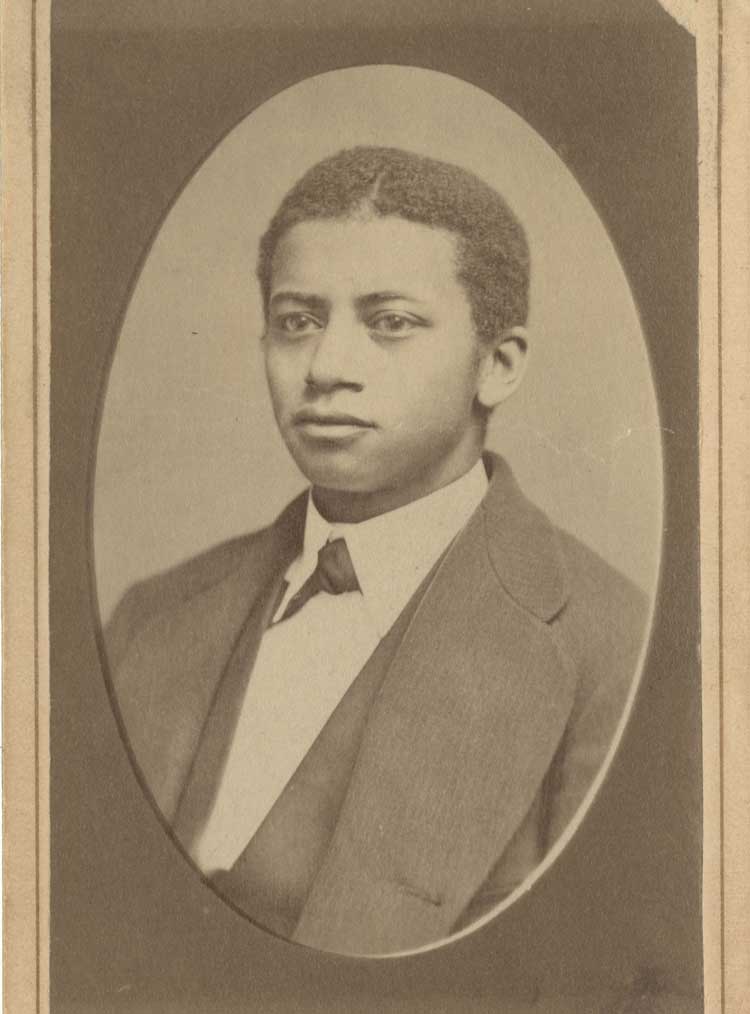

Graduated Harvard School of Dental Medicine Class of 1869

Robert Tanner Freeman was the first African-American to receive a degree in dentistry from an academic institution. Freeman was born around 1846 in Washington, D.C. He trained under Dr. Henry Bliss Noble, who encouraged him to formally train for a dental career. Freeman applied to two schools, and was rejected on racial grounds. He then applied to the Harvard Dental School after its founding, and in March of 1869, he was one of only six to receive the Doctor of Dental Medicine degree. After graduation, Tanner moved to Washington, D.C. and practiced dentistry until his death on June 14, 1873. The Washington Society of Colored Dentists, established in 1900, renamed itself in 1909 the Robert Tanner Freeman Dental Society in honor of America's first African-American dentist.

Graduated Harvard School of Dental Medicine Class of 1870

Second African American to graduate from Harvard School of Dental Medicine

First African American Faculty Member at Harvard University

Born in Oswego, New York on September 15, 1846, George Franklin Grant was the son of former slaves. He worked as an apprentice to a Dr. Smith in Oswego, and in 1867, began his studies at Harvard Dental School. Grant graduated in 1870 with the degree of Doctor of Dental Medicine. Dr. Grant was the second African American to graduate from the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, and the first African American faculty member at Harvard University.

He was appointed Assistant in the department of Mechanical Dentistry at Harvard Medical School in 1871, and in 1874, was named Demonstrator of Mechanical Dentistry. From 1884 to 1889, he was Instructor in the Treatment of Cleft Palate and Cognate Diseases. He treated patients with congenital cleft palates, and developed a prosthetic device to aid speech. Dr. Grant was also the personal dentist of Harvard University President Charles Eliot, as well as an inventor. He is credited with patenting the first wooden golf tee. Grant worked until six months before his death in 1910.

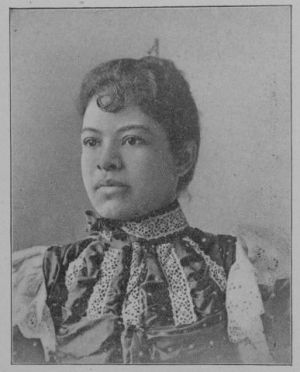

Ida Gray Nelson Rollins was born in Clarksville, Tennessee on March 4, 1867. After her mother’s death, Ida was raised by her aunt, Caroline Gray, in Cincinnati, Ohio. Gray supported her family (one son, and two daughters in addition to Ida) by working as a seamstress and housing foster children. Throughout high school, Rollins worked in the dental offices of Jonathan and William Taft, where she gained experience crucial to passing the entrance exam into the University of Michigan Dental College. Gray enrolled in October 1887, and graduated in 1890, as the first Black woman to graduate with a Doctorate of Dental Surgery in the United States.

Ida opened a private dental practice in Cincinnati, Ohio, and married Sanford Nelson in 1895. The couple moved to Chicago, Illinois, where Ida was the first Black person, male or female, to practice dentistry in Chicago. After her husband’s death in 1926, she married William Rollins in 1929. She died on May 3, 1953 in Chicago, Illinois.

To learn more about Ida Gray Nelson Rollins, visit: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/rollins-ida-gray-nelson-1867-1953/.

George Blue Spruce Jr. was born on January 16, 1931 at the Santa Fe Indian Hospital School. When Dr. Blue Spruce graduated from Creighton University School of Dentistry in 1956, he was the first American Indian person to graduate from dental school. Throughout his career, Dr. Blue Spruce has recruited and trained other American Indian people to enter dentistry and serve those living on American Indian reservations.

Dr. Blue Spruce spent 21 years in the Indian Health Service, worked with the World Health Organization in South America, wrote drafts of legislation of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act of 1976, and served as assistant surgeon general and director of the Indian Health Service for the Phoenix area. He is currently an assistant dean at the A.T. Still University/Arizona School of Dentistry & Oral Health in Mesa, Arizona, and founder of the American Indian Dental Association.

Learn more about Dr. Blue Spruce in his memoir, Searching for My Destiny.

“I spent my growing up years at the Santa Fe Indian School, with the exception of several years during World War II when my dad was in the Navy and we moved out to California.”

“My mother and father were of the generation that was forced into the federal boarding schools to be assimilated into the mainstream of society.”

“I was the first American Indian to be enrolled at Creighton University. And I began to realize that it was going to be very much living in a fishbowl, with everybody observing me and what I was doing as an American Indian.”

“I was the first director of the Indian programs that were implemented under Section 774(b) of the manpower development legislation of 1971, where for the very first time the federal government was going to recruit ethnic minorities, underserved populations, and women into the doctored health professions.”

“When I got out to the American Indian reservations, they had no running water or no electricity, and so I had to beg, borrow, and steal from the public schools to be able to practice dentistry.”

“After the Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975, I was asked to write the legislation for Title I of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, and that was to initiate scholarships for American Indian students interested in health careers.”

“I looked behind me, and I saw very few American Indians going through to become doctored health professionals. And so I thought that I would think very seriously about an organization that would help promote that effort.”

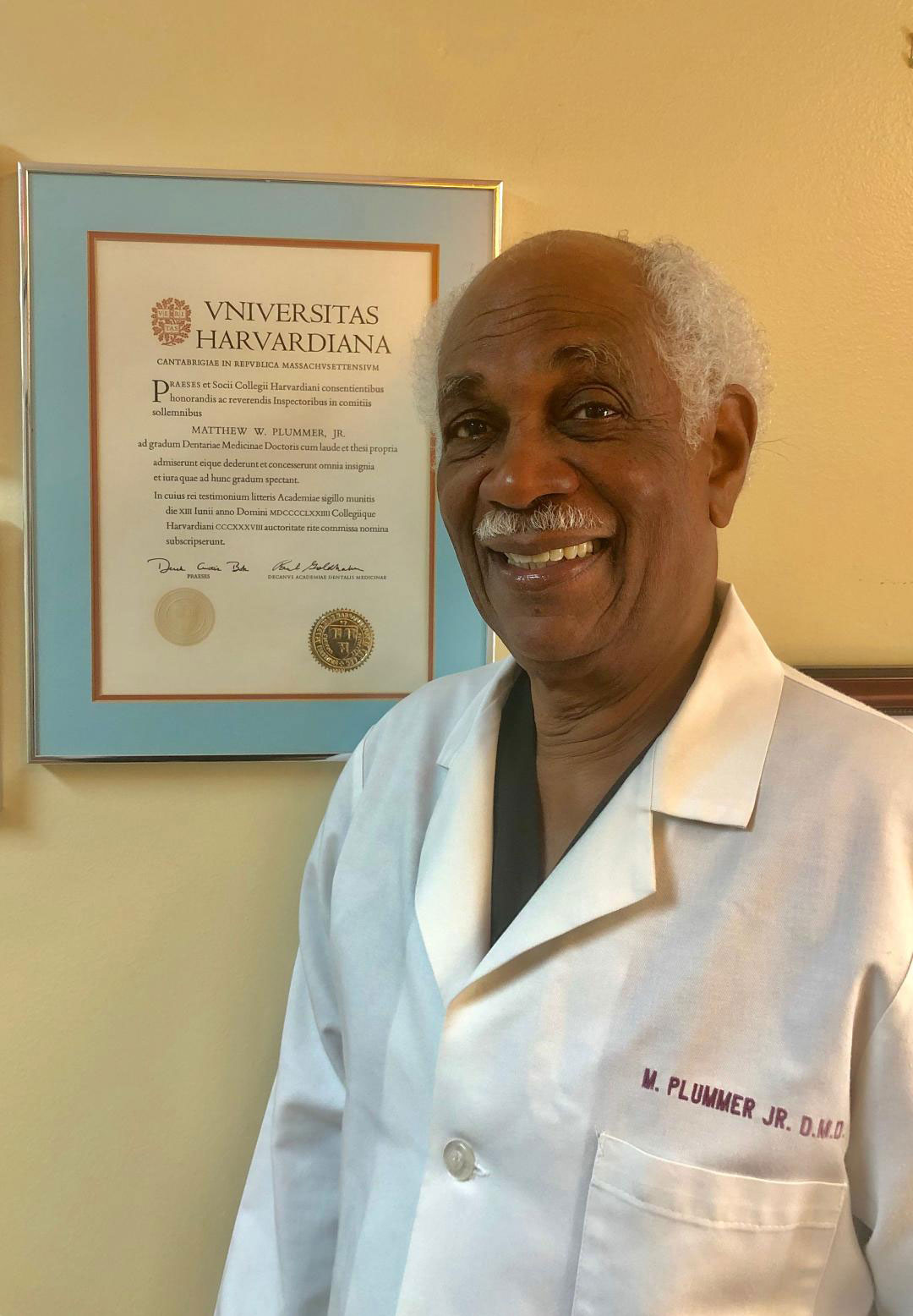

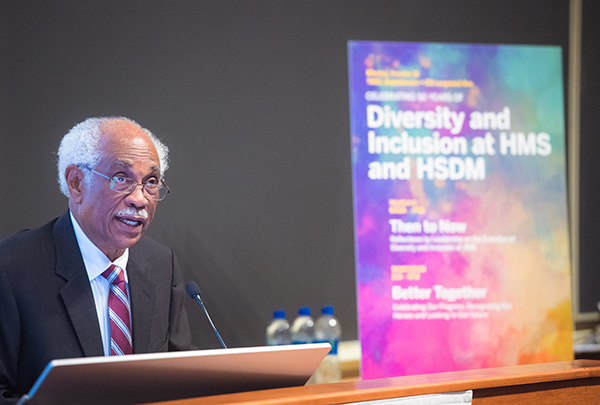

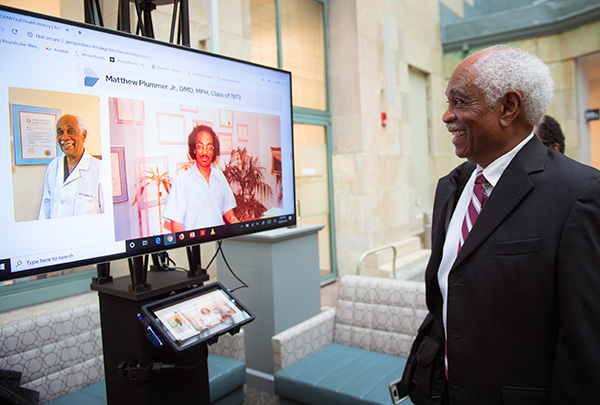

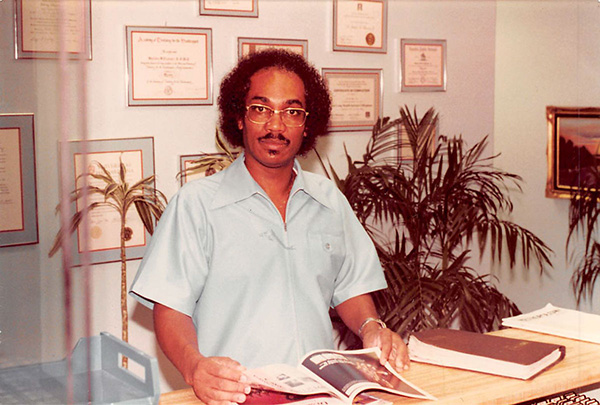

Graduated Harvard School of Dental Medicine Class of 1973

Matthew W. Plummer, Jr. grew up in Houston, Texas, in a segregated community in the 1950s and 1960s. Graduating summa cum laude from Phillis Wheatley High School in 1961, he entered Morehouse College graduating in 1965 with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and a minor in biology. After teaching for two years in Kenya with the Peace Corps, and a year and a half in the Houston public school system, Matthew Plummer entered Harvard School of Dental Medicine in 1969. He was among the 16 students comprising the first class of diverse students at HMS and HSDM, earning a Doctor of Dental Medicine degree in 1973 and a Master of Public Health degree from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Dr. Plummer conducted the first study of dental care for the developmentally disabled population in Texas. In 1979, Dr. Plummer entered private practice in his home city of Houston and he continues to practice today, providing dental services to under-served populations in the Harris County Hospital District. Dr. Matthew Plummer, Jr. is President of Cosmetic Dentistry of Texas.

“I grew up in Houston, Texas, in a segregated community.” (time)

“I guess 11 to 12, my mother took me to a dentist who had never done braces before, but he wanted to try to do braces. And so I was one of his first patients.” (time)

“I left Morehouse in ’65, joined the Peace Corps, and I had a two-year tour in Kenya, East Africa. That was also an interesting experience. I’d never been out of the country before, obviously, and I’d never been -- I had never been north before. I hadn’t been anywhere, actually, before I went to Morehouse.” (time)

“My mother said, “Apply to Harvard.” And I clearly remember telling Mama, I said, “Mama, Harvard is not gonna accept a black kid with a big afro.” And she said, “That’s OK, son. Apply to Harvard.” And, of course, in those days, what your parents told you what to do, you did it, right?” (time)

“After my acceptance, Jim Mulvihill … came to Houston. We talked about finances, how I would finance my dental education. And he said … he was working on a situation that would help me alleviate some of the cost. And that situation was he had contacted Wellesley College to see if they could employ my wife and I as house parents. And that came through: my wife and I were the first house parents at Wellesley College.” (time)

“I also served as a minority recruiter for the Medical School, the dental school, and the School of Public Health.” (time)

“And to be referred to as Black Panthers was extremely shocking, because, you know, we thought Boston would be different. We thought Boston, the bastion of liberalism, surely the racist experiences that we were accustomed to in the South would surely not be prevalent in Boston.” (time)

“I think it was ’72 to ’74. While I was at the dental school, I realized, and we all realized, there were very few black and brown students at the -- at Harvard Medical School and Harvard dental school.” (time)

“That project actually served as the blueprint for the explosion of minority programs in predominantly white dental schools across the country during the, you know, the late ’70s and early ’80s.” (time)

“We also did a survey of dental services for non-institutionalized developmentally disabled persons in the state of Texas.” (time)

“Harvard has an obligation to continue the diversity program in the years to come.” (time)

Graduate Harvard School of Dental Medicine Class of 1974

Dolores Mercedes Franklin was the first African American woman to graduate from Harvard School of Dental Medicine. She earned an MPH at Columbia University in a joint degree program with Harvard and was a postdoctoral clinical fellow in Dental Public Health at HSDM. Dr. Franklin blazed the trail as assistant dean at New York University College of Dentistry, the nation’s largest dental school, and was the highest ranking dental executive at the former Sterling Drug, Inc. She has been an assistant commissioner in New York City (NYC) and had dual reporting to the NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation, the nation’s largest urban healthcare agency. Dr. Franklin became a consultant and researcher for the U.S. Department of Labor and the Colgate-Palmolive Company, a clinical professor, an author, and an advocate for oral health as integral to overall health.

First African American Interim Dean at Harvard School of Dental Medicine

Dr. Joseph L. Henry was Professor of Oral Diagnosis, before becoming the first African American to become Interim Dean at Harvard School of Dental Medicine. He earned his degree from the Howard College of Dentistry, and his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois. He became Professor at Howard University of Dental Medicine, as well as Director of Clinics and Coordinator of Research. In 1966, he was appointed Dean of Howard University School of Dentistry. In 1968, Dr. Henry established a dental clinic at Resurrection City, the tent city in Washington D.C., as part of the Poor People’s Campaign initiated by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In 1975, Dr. Henry was recruited to Harvard School of Dental Medicine. He was the first Black professor on the Harvard School of Dental Medicine faculty.

From 1990-1991, he served as Interim Dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine. The Joseph L. Henry Oral Health Fellowship in Minority Health Policy has been established at Harvard Medical School by Delta Dental and private contributors. This Fellowship continues his legacy by providing resources for the next generation of leaders who will improve the capacity of the health care system to address the health needs of minority and disadvantaged populations.

First Woman Dean of an American Dental School

Dr. Jeanne C. Sinkford was born in 1933. She enrolled at Howard University where she initially studied psychology and chemistry, and pursued a career in dentistry. She is an internationally renowned dental educator, administrator, researcher, and clinician. She served as Dean of Howard University College of Dentistry from 1975 to 1991, where she was the first woman to be dean of an American dental school. From 1992 to 2011, she was responsible for diversity programming and initiatives at the American Dental Educational Association.

First American Indian Woman Dentist

Jessica A. Rickert, DDS, is the first American Indian woman dentist. She earned her Doctor of Dental Surgery in 1975 from the University of Michigan School of Dentistry. She was a general dentist in private practice and the director of the dental clinic for the Children’s Aid Society in Grand River, Michigan. In 1982 she opened her private practice serving the Interlochen, Michigan area for 30 years. In 2009, Dr. Rickert was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame for being the first American Indian Woman Dentist world-wide.

Director, National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care

Dr. Reuben C. Warren earned his undergraduate degree from San Francisco State University, and his dental degree from Meharry Medical College. He also earned his MPH and PhD from the Harvard School of Public Health, as well as a Master of Divinity from the Interdenominational Theological Center.

He is currently the Director of the National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care and Professor of Bioethics at Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Alabama. From 1988-1997, Dr. Warren served as Associate Director for Minority Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“My interest in dentistry really was trying to resond to unnecessary suffering, not life or death…People are really attentive about life or death situations, but suffering is something that’s overlooked, so I really felt that I wanted to do something to reduce the suffering in populations who I viewed were suffering the most, including me.”

“Meharry chose me…in being at Meharry, I understood that dentistry was a small picture. The bigger picture was community oral health.”

“I realized at my time at Meharry that one-on-one, one patient at a time was not going to do it. So I looked for a way to engage in population health, and that brought me into formal education in public health.”

“Oral health needs are met after systemic health needs are met; so you just can’t go directly to oral health without going through the whole gamut of health concerns.”

“Upon graduating from Harvard School of Public Health and finishing the residency, I joined the faculty of the University of Lagos, a relatively new dental school. It was part of the medical school.”

“I was able to look at the foundation for people to have hope when hope seemed hopeless and to have faith when faith seemed impossible, and it was very inspiring…It helped to broaden my description of health…I understood from my seminary and other limited experience that spirituality is a critical part of health – not religion, per se, but spirituality.”

“We need to rethink what health is and spend less time defining it and more time describing it and then design strategies based upon that broadened description of health.”

“Perfection is always the goal, and you can’t lose sight of what you think perfection ought to be, and in the midst of disaster, despair, it gets muddled, and if you lose that vision, you become part of the problem as opposed to part of its resolve.”

Graduated Harvard School of Dental Medicine Class of 1989

Growing up in El Salvador Sonia Molina knew that dentistry was in her future. Fleeing political turmoil, she and her mother and siblings moved to California when she was 17 years of age. Sonia Molina attended California State University, Long Beach, where she graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Biomedical Sciences. She then matriculated at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, receiving her Doctor of Dental Medicine Degree and Master of Public Health Degree. She completed her postdoctoral studies in Endodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry. Dr. Molina is President of Molina Endodontics, a dental office specializing in internal oral surgeries.

“When I was in El Salvador, I was already planning on going to dental school. In El Salvador, most of the dentists are women”

“My father died when I was five, and my mother only completed high school. … So it was very hard for her to get a job in El Salvador.”

“It came down to two schools at the end. UC-San Francisco, and Harvard. And, they were both, at that time, considered like the top two schools in the country.”

“You know, I started noticing things like that, that here, I hadn’t really noticed.”

“So they said, you know, you have to repeat the year or leave. And so I met with Dr. Henry. … I couldn’t come home and say, I fail, because a lot of the people in my community, in my church, they were looking up to me...”

“Then second year, it got easier, and third year, I was coasting; I was getting honors because by then, I was working with patients… it was more meaningful than just reading books.”

“I became an endodontist; I opened my own practice, again, not knowing what I was getting myself into.”

“I helped start a group called SALEF, a Salvadorian organization that helps Salvadorians with money to go to college, and also does things like civics, engagement, get out the vote, literacy programs, basically help the community become integrated into the mainstream community.”

“I feel very strongly … that education is the way of getting out of poverty.”

First Woman President of Chicago Dental Society, First Woman and African American President of American College of Dentists

Juliann Bluitt Foster (1938-2019) received her bachelor’s degree from Howard University in 1958 and her dental degree from Howard in 1962. She joined the Northwestern faculty in 1967 and was affiliated with the dental school until its closure in 2001, retiring as professor emerita. She served as president of the Chicago Dental Society, the first woman to hold the position, from 1992 to 1993. In 1993, she became first woman and African American president of the American College of Dentists. For 28 years, until retiring in 2008, she served on the board of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois.

Associate Dean for Prevention and Public Health Sciences and Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois, Chicago College of Dentistry

Dr. Caswell A. Evans Jr. DDS, MPH, is Associate Dean for Prevention and Public Health Sciences and Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois, Chicago College of Dentistry.

Dr. Evans was the executive editor and project director for Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General, released in May 2000. He directed the development of the National Call To Action to Promote Oral Health, released in April 2003.

Dr. Evans served as Director of Public Health Programs and Services for the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services for twelve years. He also served as director of the County Division of the Seattle-King County Department of Public Health in Washington State.

He is a past-president of the American Public Health Association and the American Association of Public Health Dentistry. Dr. Evans is a diplomate of the American Board of Dental Public Health and a past-president of that Board. He was elected into the Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences in 1992.

Dr. Evans is a graduate of Columbia University’s School of Dental and Oral Surgery in New York City, and he earned his masters of public health degree from the University of Michigan.

Assistant Professor of Oral Health Policy and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine

Dr. Brian J. Swann is Chief of Oral Health Services for the Cambridge Health Alliance and conducts the Oral Physician Program within the General Practice Residency Program. At the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, he is Assistant Professor of Oral Health Policy and Epidemiology.

Dr. Swann graduated from the University of California, San Francisco, School of Dentistry. After practicing for 30 years in California, he switched gears to focus on public health and dentistry, and became the first Joseph L. Henry Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard Medical School. He received a Master of Public Health degree from the Harvard School of Public Health and was presented with the Albert Schweitzer Award in recognition of his commitment to global outreach.

He is involved with projects in Boston Massachusetts, Jamaica, and Rwanda, and developed an oral health care education project for the Wampanoag Tribe on Martha’s Vineyard, a Massachusetts island.

“So the, UCSF had a large contingency of black employees, and when they did not see students of African descent in the student body, they went on strike.”

“When I got interviewed, the assistant dean, said, ‘Where else did you apply?’ I said, ‘Nowhere else.’ She said, ‘Oh, that’s too bad.’ I said, ‘Why?’ and she ways, ‘Because your faculty doesn’t want to teach people like you. And if you have another option, I advise you to take it, because you’re going to catch hell here.”

“I did get accepted by the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University. But I did not get accepted initially by the School of Public Health.”

“… one of the vice presidents of the California Boards said that, ‘you know, you guys might bully your way through dental school, but you will not pass the California boards.”

“So I put the instruments that I needed and boiled them for 30 minutes, and extracted her tooth at the kitchen table.”

“He called me up, and says, ‘Brian, I see that you want to hold off for a year. That’s fine. But let me tell you what’s behind door number two.’ ”

“I took them to Kenya and to Zanzibar on one trip, and we also got together and I took them to Ethiopia for the first international dental conference in that country, of 76 million people that only had 48 dentists.”

“…and so Harvard Dental School now does a lot of global oral health projects, which I’m happy to say I was part of the team that initiated that.”

“…when I said the word dentist, it seemed like everything just went towards teeth, and I have a problem with that, because we are doing more than just teeth.”

“I want the patients to be confused, to a point, in order to ask the question, what is an oral physician?”

"We started the program in a collaboration with Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, the Wampanoag tribe, and Harvard School of Dental Medicine.”

“The number of African Americans to come through Harvard Dental School has been very, very dismal, and small.”

“I mean Rwanda, we started this program, had 25 dentist for 11 million people. Now they have 40 dentists that we’ve graduated.”

“If you only come here to learn how to fix teeth, then you need to go somewhere else. Because Harvard prides itself on training leaders…”